Homecoming royalty are more popular than they appear

LESSON: Rather than let the word “NO!” close doors to you, react with “Challenge accepted. You’re ON!” and reach higher.

At my school, popularity trumped talent. You were as likely—or unlikely–to be cast as the lead in school plays or be named prom queen as become a writer on the school paper.

And being shy and driven, I wasn’t social catnip. Not even close.

Yet somehow I managed to become a successful journalist. I just did it my way.

I was far more likely to tutor football players than date them.

Not to sound obnoxious (OK, to sound über obnoxious), but I launched our school’s literary magazine and was an editor at the nerd bastion known as our yearbook.

Aw, my first review–and no, I didn’t write it! But I may have staged that photo–literally.

The yearbook staff–not a cheerleading tryout.

The ambition, audacity and naiveté of youth also spurred me to march into the newsroom of the city’s leading newspaper.

My goal: convince an editor that their Saturday Page 2 was dead space—and that I had the solution. I proposed the paper run creative writing by students at the city’s high schools.

As if, right?

Astoundingly, he loved the idea, and “Generation Rap” was born.

I found volunteers at the other high schools to round up fiction. Naturally, I gathered my school’s creative writing, and my short stories ran regularly, along with those of other students.

Shy yet ballsy. Odd combo, but that was me in high school.

We weren’t paid, but who cared? We were in the city newspaper! And I had clips for my portfolio, which I needed to get a job as a professional journalist.

I didn’t make Page One till freshman year of college. Say is that a sudoku?

Of course, I had to top that feat as a college student. While home for the summer, I applied to be fashion editor.

I owned just two skirts, a few tops and one pair of jeans—essentially my entire wardrobe for a decade. Fortunately, the editor-in-chief never noticed.

Does the top look familiar? College–and fashion editor attire. (Dorothee Bis bag costs extra.)

The first story he assigned me was to interview the city’s most successful designer-boutique owner. I didn’t tell him we shared the same last name because she was my mom.

But she deserved the focus. She was charming, had a British accent and had brought top-tier brands to our city. She was a local institution.

My mom — elegance personified.

As a former journalist, she also had a well-rehearsed, polished script from doing radio and other interviews. But unlike other reporters, I had nearly two decades of first-hand research, and I wasn’t about to settle for the same old story.

The editor was delighted with the resulting profile—and my mom probably gained respect for me.

I resigned at summer’s end to return to college, a good thing since my paychecks remain MIA.

Checkmate

I wish I had a copy of that story, as well as a Page 1 exposé I wrote for my university newspaper. (They didn’t care about social standing.)

That exposé changed how FedEx Office—then called Kinko’s—did business.

Yes, FedEx, I was the one. My bad.

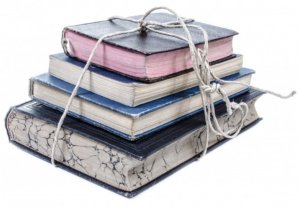

To spend or not to spend, that is the question.

It bothered me that authors weren’t getting paid their due. So I called the American Booksellers Association and American Library Association.

Neither was amused.

I knew I was hurting myself, given the three tomes weekly I read as a double major in French, and French, Spanish and English Dramatic Literature. But author rights were right.

The week after the story appeared, a previously unapologetic Kinko’s changed its policy. It would no longer allow photocopying of books—nationwide.

Great news, even though I had to buy all my textbooks and show my driver’s license to photocopy my own articles at—oh, the irony, FedEx.

Willkommen, bienvenue, bienvenido, welcome to my discretionary income.

So much prettier than photocopies.

As they say, truth is more expensive than fiction—or something like that.

But more importantly, only you can be you. So own it, revel in it and help others do the same.

And bring your I.D. to copy shops.

Leave a Reply