Sightseeing in Belfast. (My photo).

THE LESSON: Never stand next to a man with a gunshot wound in his face.

You could call it my Years of Living Recklessly.

YOUR TIME IS UP, NO. 1: As a young reporter, I decided to enter a killer-rapist-pizza chef’s house when assigned to interview him.

I realized I couldn’t talk with him outside as my Dallas newspaper editor suggested, due to the six cops surrounding his house.

Once I realized the situation–hard to miss the cop cars—I called everyone with his last name to find his mother, and I brought her with me. I hoped and prayed he wouldn’t kill me in front of her. I interviewed him for an hour though he kept pacing barefoot and repeating “I’m not innocent. I’m not innocent.”

Say, how many knives does a pizza chef need, and where’s the missing one?

I couldn’t help notice the array of chef knives on his kitchen counter, visible from my seat.

Then the cops, pistols drawn, stormed the house. That was when I thought I’d die.

YOUR TIME IS UP, NO. 2: As a Page One reporter for the same Dallas newspaper, my job was to clobber the competition. And that meant getting the story first and better. But when an editor told me and a fellow reporter that one of us needed to go into the barrio to find and interview another murderer—neither of us wanted the byline.

We stood in the newsroom volleying reasons why we shouldn’t go (code for why we should live). Back and forth we went until she said she was a single mother. I couldn’t beat that. I got my car keys to head out.

Such a darling boy, his first birthday.

Abruptly, she said she’d go. She was gone for two hours and received a hero’s welcome upon her return, despite a failed mission.

Later she told me she’d volunteered because she realized I actually would go door-to-door in the barrio.

She’d gone shopping.

Did you say there’s a huge sale at Saks and Zara? Be still my heart.

YOUR TIME IS UP, NO. 3: A newspaper sent me to Great Britain for a month and I wrote 40 stories on everything from the homeless to politicos in England, Scotland and Wales.

I stayed in a two-barbwire hotel.

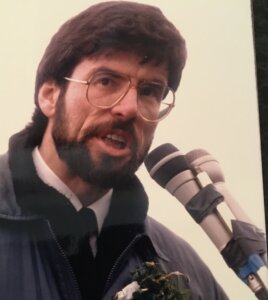

Did that stop me from going to an IRA funeral at the invitation of Gerry Adams, head of the Sinn Fein? No, of course not. (See: foolish youth.)

Don’t stand so close to me–if you’re smart. (My photo.)

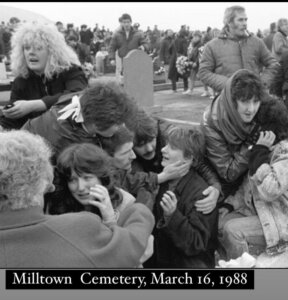

As I stood as near to him as possible, the sound of fireworks—gunfire—drowned out the solemn rites. Gravestones exploded into dust—and we were like the ducks you shoot down at a county fair. I realized two gunmen lobbing grenades were trying to assassinate Adams—the man who had a crater in his cheek from the last such attempt. I plunged into the mud first, shielded by two bodies on top of me. My first thought was I’m not Irish. The second was I seriously could die–actually die—nonetheless, and posthumous awards are meaningless.

But then the gunfire stopped.

They carted out the newly dead and gravely injured in the carts that had brought in the coffins. The funeral resumed. This was Belfast, after all, and The Troubles had ceased to detonate fear among the locals.

That should’ve been my cue to exit. But no, I stayed, hanging onto Adams’ every word.

The funeral earned its own Wikipedia entry.

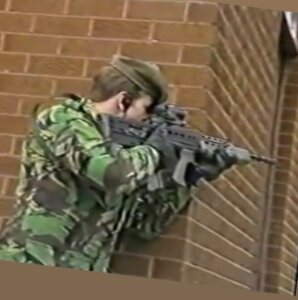

Then the gunfire resumed. I spotted a gunman on top of a building pointing his rifle at me—well, Adams.

Same rifle, different shooter.

The next 15 minutes seemed to last a lifetime. In some ways it was like the worst annual job evaluation ever. To the sounds of rat-a-tat-tat, I reviewed my questionable decisions—such as going to Belfast during The Troubles. I decided that if I survived, I needed to become a better person.

I was fortunate. My slacks were shredded by shrapnel but I didn’t have a scratch. I later discovered I’d written down in my notepad every word people had said. Confirmation came from the local paper, which oddly ran a photo of my hand atop a gravestone taking notes.

Three people died and 72 were injured. Adams was fine. Of course. ‘

Not a toy.

I was petrified but stayed, interviewing people from all faiths and walks of life over the next two days.

My stories ran on page one of newspapers across the country, including the Chicago Tribune and the Providence Journal.

The better news: I’d live to read those stories.

And the best news of all was that I decided to retire from mortal combat. That was my last reportorial dance with death. And I’m far better for such changes to my life.

Page One everywhere? It’s a reporter’s dream–and potential nightmare.

Leave a Reply